By DW

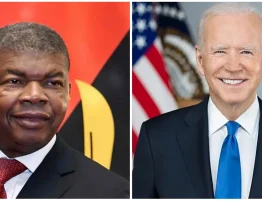

No one believed the new president of Angola, Joao Lourenco, when he promised thorough reforms. But the man once considered to be a puppet of the old regime has turned out to be as good as his word. Or has he?

A few days before Christmas, President Joao Lourenco struck again: he replaced the administrations of nine public utilities and companies, adding them to a dozen where he had already taken similar action, including the central bank, oil, the diamond industry and the media. The officials had all been appointed by his predecessor Jose Eduardo dos Santos, who used nepotism and patronage to perpetuate his power.

To Angolans, the latest replacements looked like a mere afterthought, coming in the wake of Lourenco’s most spectacular dismissal so far. In November, three months after his election to succeed longtime ruler dos Santos, Lourenco sacked the former president’s daughter Isabel dos Santos from the leadership of the state oil enterprise Sonangol. The country’s economy is almost completely dependent on oil revenues. Accordingly, President Lourenco called Sonangol “Angola’s golden goose,” and announced that he was going to take “good care of it,” implying that this hadn’t been the case so far.

A princess dethroned

Isabel dos Santos is still considered to be one of Africa’s richest and most powerful women. But she is no longer untouchable. Her swift downfall was compounded by the announcement in Angolan media that Sonangol was launching a probe against her on suspicion of misappropriation of public monies. Sonangol has meanwhile denied this, saying the purpose of the auditing currently taking place is to ascertain the company’s situation. But according to news agencies, Sonangol’s spokesman Mateus Benza had said earlier “We are verifying possible misappropriation, but I can’t yet confirm anything.”

President Joao Lourenco has taken other steps towards reform, including granting a temporary amnesty to rich Angolans willing to repatriate their funds. And he threatened to take legal action against those who won’t comply. Nobody knows exactly how much money the elite is hiding abroad, but Angolan economists have put the total at $28 billion (€23 billion), which amounts to more than the country’s international reserves.

Time to tackle the real problems

Angolan sociologist Paulo Ingles is not convinced. In an interview with DW, the researcher from the German University of Bayreuth pointed out that Angola’s sovereign fund is still headed by a son of dos Santos. According to Ingles, there are credible accusations of mismanagement and self-enrichment against this dos Santos offspring known as Zenu. Exonerating him would hardly be enough. “The president should order a probe. Then we could leave behind the politics for show and start working on the real problems,” Ingles said, pointing out that this would also counter the suspicion that Lourenco is just placing his own people in strategic positions to bolster his hold on power.

How tenuous this hold could turn out to be is explained by political anthropologist Jon Schubert from the German University of Leipzig. Until now Lourenco has limited his attacks on the economic interests of the former president and his close circle. “This ensures him popular support, but also the support of an important part of the ruling party that was dissatisfied with dos Santos. But there are other economic interests, military and party interests. They will probably hold out for a very long time. It is too early to say whether he plans to curtail these too,” said the researcher and author. It is also too early to say whether he will be able to introduce a political culture of transparency and accountability, assuming those are his plans. For Schubert, it is nevertheless in the interests of the governing MPLA (Movimento pela Libertacao de Angola) to support the new president, since only a perceived renewal of the party will ensure that it stays in power.

A former president to be reckoned with

But if the party can benefit from Lourenco, the new president also badly needs the support of his party. Although Jose Eduardo dos Santos stepped down as head of state, he has not relinquished his position as leader of the MPLA. This could become a problem for the new man in Luanda, says Peter Meyns, political scientist at the University of Duisburg-Essen. “In the end he will have a free hand governing only if he assumes the party leadership in the short run. But as of now, it doesn’t look like it,” Meyns told DW.

Jose Eduardo dos Santos, aged 75 and suffering from poor health, announced that he will retire from politics in 2018. Until then he intends to keep the presidency of the MPLA as a guarantee of his protection. It remains to be seen whether he will truly relinquish all power as promised. The man who ruled the country for 38 years is well known for changing his mind at his own convenience.

Meanwhile, according to German researcher Peter Meyns, expectations are high among the population. In Angola “the gap between rich and poor is very wide. Dos Santos never really cared about the needs of the people. More is expected of Lourenco. He will have to act to shrink the gap, but that cannot happen from one day to the next,” Meyns said.

Wait and see

Some of Lourenco’s moves seem tailored to win popular support. Budget cuts recently announced by the presidency take aim at lawmakers’ and ministers’ perks and benefits. In a country that has been ruled by the same party since independence from Portugal in 1975, and where the opposition has few prospects of ascending to power in the near future, the ruling classes are under general suspicion of corruption, nepotism and greed.

Angolan sociologist Paulo Ingles is probably speaking for many of his countrymen when he says with evident skepticism, but also with a little bit of hope: “We are in transition. It’s not the future yet but neither is it still the past. We’ll just have to wait and see.”