AFW2017090857105485 Lisbon Africa Monitor in English 08 Sep 17

[Article by Paulo Guilherme: “Angola: UNITA and CASA-CE Between Extreme Positions of Regime and Civil Society”]

1. The expectations of the international community, shared by Angolan civil society, that the regime would recognize irregularities in the electoral process, leading to a more transparent assessment of electoral results, and resulting in a rise of the voting and parliamentary representation of the opposition, were put to an end on 06.Sep, with the announcement of definitive national results of the general elections (23.Aug), which generally maintain the distribution of votes announced by the National Electoral Commission on 25.Aug.

The regime’s intransigence over concessions to the opposition had also been expressed during the proceedings of the Provincial Electoral Commissions, which the opposition considers to have been made in disregard of the law. From the perspective of the opposition, and from sectors of civil society, the counting exercise at the provincial level aimed solely to match the final results, announced on 06.Sep, with the provisional ones, from whose tallying the opposition delegates at CNE were excluded. Between political and independent agents of civil society, the general perception is that the CNE’s action in the process favored the MPLA, ignoring or even collaborating in irregularities.

Despite efforts by the opposition, especially UNITA, to moderate its objections, in order to avoid accusations of violence, the level of criticism of the instrumentation of the CNE and other state institutions by the MPLA is considered unprecedented, especially due to an amplification through social networks, greater politicization of the population and greater political maturity and/ or awareness of civil rights. The weak economic and social situation, along with the media exposure of cases of corruption involving the political class linked to the presidential family and the MPLA, is also a significant factor in the trend.

Parallel to criticism of the process, messages calling for demonstrations and violence have been circulated by unidentified groups, prompting the US embassy in Luanda to issue a warning to US citizens in the country. The Interior Ministry has responded to protest attempts with a visible reinforcement of police security, including special antiriot forces, with a deterrent effect on the outbreak of spontaneous protests. The calls issued have so far not resulted in effective mobilization by demonstrators. The authorities have also, through public statements, sought to feed the idea that police and/or military force will be launched against demonstrations. On the morning of 07.Sep, a plane flying at low altitude over Luanda again spread leaflets equating the refusal of the electoral results to leading the country back to war.

The parties themselves are under pressure from young and/ or radical internal wings, as well as from non-militants who have openly supported the opposition, to organize protest rallies against the election results. On 05.Sep at UNITA’s headquarters in Viana, Luanda, c.100 young people concentrated outside, urging the leaders of the party, gathered inside in a Political Commission meeting, to support the convening of national demonstrations. Party leader, Isaias Samakuva (IS), addressed them at the end of the meeting, calling for calm.

UNITA held demonstrations against CNE irregularities in the preparation of the electoral process in Jun, throughout the country. Due to the great participation and potential for clashes with police forces that could be used against UNITA, the party exercised great control of the demonstrators. At the current juncture, given the level of discontent, party sources consider high the risk of disruption at a similar event.

At a demonstration by civil society in 2013, protesters came to be face-to-face with antiriot police, with firearms at them. A last-minute intervention by opposition leaders, including IS, among protesters who refused to halt the march, prevented the protest from ending in bloodshed. At the time, the opposition feared that the protest would also be used to decree the state of emergency and eliminate party leaders.

2. The strategy pursued by UNITA is to exhaust all forms of legal recourse, before resorting to protests. The request for a challenge to the Constitutional Court, an institution with a past of support to the regime, should lead to another rejection of the opposition’s arguments. Publicly, UNITA is conditioned on having to maintain its institutional stance, with verbal restraint (avoiding the use of the word “fraud”, calling for “recount” of votes by the CNE instead of “rejection”), but also risks to discredit itself with vast sectors of society that supported the party in the last elections because it presents greater possibilities of bringing about political change. These sectors include young people from poor neighborhoods of the outskirts of large cities (Luanda, Benguela, Huambo).

Like CASA-CE, whose results (just above 9%) are considered internally and in diplomatic circles to be unreliable given the level of adherence to coalition initiatives, the UNITA leadership is on an internal consultation phase, about how to proceed after the disclosure of the final results. The CP/ UNITA met again on 06.Sep, after the opposition leaders issued a joint statement against the handling of the electoral process by the CNE.

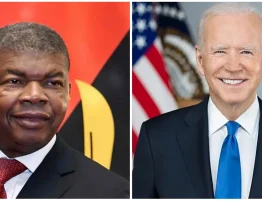

In relation to the inauguration of Joao Lourenco, initially expected to take place at 20 or 21.Set., party sources believe that the opposition will not be present as a form of protest.

More divisive internally is the decision to take up the party’s seats in the National Assembly (AN) in Oct.. If they take office, opposition parties risk further discredit by critical sectors of society and, consequently, losing ability to mediate; At the same time, for some elected MPs, as well as for the party, the entry into the AN is a necessary source of subsistence through salaries and subsidies. The two main opposition parties are in consultations on the use of these forms of protest.

Diplomatic sources are most likely to see an intermediate solution, in which opposition MPs take their seats in parliament not on schedule, but only later, as a form of protest.

3. At the level of the opposition parties, the strategy followed until the provisional results were announced by the CNE – protest against irregularities, but proceed, creating conditions for a more rigorous inspection than in previous elections (UNITA had 49 thousand accredited electoral inspectors) – is interpreted as a success in exposing the control of State institutions by the MPLA, but as having led to a situation of impasse: with the commissions submitting to the CNE for national tabulation, minutes that do not reflect the counting of the votes of all the polling stations (in the case of Benguela, 20,000 votes were excluded from the tabulation), even with the opposition refusing the vote at the provincial level in 14 of the 18 provinces, the value of the summary minutes held by UNITA and CASA-CE is now low.

On the other hand, MPLA’s strategy, prior to the elections, to condition the process and subsequently facilitate entry to observers and missions with a low level of demand in electoral processes (UA, CPLP, Portuguese parties), while not creating the conditions for the participation of the European Union and observers called by the opposition, has proved to be effective in validating the process at international level, even though the work of observers is practically limited to the functioning of polling stations, where problems were limited.

4. On the part of the opposition, moderate expectations remain regarding a national and/ or international mediation effort that could force the regime into concessions, above all in terms of the democratic functioning of the institutions. The decision by the Supreme Court of Kenya to invalidate the results of the last presidential elections and order a repeat of the vote (in Oct) raised expectations that the degree of transparency requirement in African elections in general, including Angolan elections, may be greater by the US and the EU in particular.

Regarding the US and EU, the respective declarations on the Angolan elections should be issued only after the TC has ruled on UNITA’s appeal. Diplomatic sources say that the EU should remain skeptical of the statement issued after the announcement of the provisional results, calling for the CNE to complete the process with transparency. At the request of the opposition parties, the EU mission in Luanda received their representatives, who reported irregularities in the process, which they consider ignored by local, mainly public, media.

In relation to the United States, civil society and opposition groups expect a support of their claims, due to the attention that the country’s diplomatic mission in Luanda has been giving to the process, visiting the CNE data center, as well as the UNITA parallel counting office, and making contact with summary records (representing 95% of the polling stations, which differ from the CNE’s results) held by the party. This expectation has been growing due to (a) the fact that Ambassador Helen La Lime is at the end of her term of office and that the nominated ambassador, Nina Maria Fite, is a former counselor at the embassy and is therefore knowledgeable of the country’s political and institutional reality; (b) that, due to disputes between the authorities/ Sonangol and the oil sector, the latter’s “lobby” in favor of the regime is inferior to that of previous elections.

Portugal’s ability to mediate is dismissed by civil society, given the congratulations upon the election of JL on the basis of provisional data. In opposition circles, the Portuguese position is interpreted as a “compensation” to the regime, in defense of the immediate (economic) interests of the country, given the recent disruption in the bilateral relationship, the result of judicial charges and investigations of regime entities, and to the fact that, contrary to previous elections, the government has kept greater distance from the electoral process, including by suspending visits of government members to the country during the period.

Internally, the expectations that the Episcopal Conference of Angola and Sao Tome (CEAST), whose influence on society the regime has been trying to reduce by promoting the emergence of new churches (Tocoist Church, Fr. Huambo, among others), less independent, can take on an active role of mediation are also mitigated by the internal divisions between bishops aligned with the regime and/ or averse to “political positions”, and others who argue that the church has a duty to denounce the problems of the population. The Vatican has received several briefings on the electoral process in recent months.

In an attempt to condition CEAST’s intervention, the regime provided for the bishops’ retreat (02.Sep), for preparation of the pastoral note on the elections, to be held at a beach house in Mussulo (Luanda) belonging to Bento Bento, 1st secretary of the MPLA in Luanda. However, the tone of the pastoral note is generally interpreted as balanced. Previous pastoral notes by CEAST on the social situation of the country stood out by their critical content.

[Description of Source: Lisbon Africa Monitor in English — E-mail newsletter distributed two to three times weekly carrying analytical reports on former Portuguese colonies in Africa and appears to have access to privileged information]